|

By ADRIAN RODRIGUEZ | [email protected] | Marin Independent Journal Novato landlords will soon be prohibited from turning away prospective tenants who use Section 8 housing vouchers when a new ordinance becomes law. After making minor changes, the Novato City Council this week voted unanimously to adopt the ordinance on its first reading, following guidelines set by county officials. A second reading and final vote is scheduled for Sept. 11. If it passes then, the anti-bias housing rule becomes effective in 30 days. Councilwoman Denise Athas thanked city staff and others who worked to bring the ordinance forward. “It’s such an important item and I think whatever we end up with, the fact that we get it passed is what’s really crucial,” Athas said. Marin’s Board of Supervisors approved its fair housing ordinance — which forbids landlords from discriminating against prospective tenants with Section 8 or other rental assistance vouchers — in November 2016. Supervisors at the time said they hoped other local municipalities would follow suit adopting similar regulations, in part so that any confusion for renters or landlords could be avoided about where, exactly, the rules apply. The Novato City Council considered a version of that ordinance in May, but ultimately held off on a decision, considering that there were concerns the regulations didn’t state clearly enough that they applied only to rental housing. At the May meeting, a representative of Nova-Ro, a nonprofit based out of Novato that provides housing to low-income seniors, told the council he was afraid the fair housing ordinance could get in the way of a requirement his organization places on its clients that ensures operations run smoothly. Prospective tenants who apply to live in Nova-Ro’s units have to prove family members or other caretakers live within reasonable distances to the organization’s housing complexes, and can be available to help out during personal emergencies. In July, the city held a community workshop to discuss options. Bob Brown, Novato’s community development director, said staff reviewed the ordinance that the Fairfax Town Council greenlighted earlier this year. The version of the ordinance presented Tuesday attempted to address all council members’ and landlord concerns, he said. “So with that, I hope we’ve hit the mark this time around,” Brown said. With regard to a section of the ordinance that deals with civil liability and what the courts can award to a person who is discriminated against, Councilwoman Pat Eklund asked if the Novato ordinance could match exactly the wording of the Fairfax ordinance. Assistant City Attorney Veronica Nebb and City Manager Regan Candelario confirmed that the edit would be acceptable. After Athas made a motion, Eklund added the amendment, and it passed 5-0. While fair housing advocates applauded the city for taking on the issue, many voiced concerns that they would like to see more consistency in rules adopted by Marin jurisdictions. David Levin, managing attorney at Legal Aid Marin, said that he serves a client who uses Section 8 housing vouchers, and she was denied housing by an apartment complex that was on the wrong side of the street, just outside the county’s jurisdiction. “The county’s ordinance applied on one side of the street,” he said. “So any opportunity to make the laws uniform across Marin really helps.” He added that after searching homes for rent in Novato, he found six listings that said no Section 8. “The discrimination issue here is very serious,” Levin said. Caroline Peattie, executive director of Fair Housing Advocates of Northern California said another issue is that the ordinance allows landlords to require that a tenant has a cosigner or guarantor who is a blood relative and within a one-hour drive of the residence. “I think that creates barriers to housing opportunities for people of color and individuals with disabilities and people who don’t have local connections, even if they qualify by income or age,” which goes against the purpose of the ordinance, Peattie said. “So there is a little bit of contradictory language within the ordinance.” Novato resident Peter Mendoza, who uses a wheelchair and once benefited from the Section 8 housing program, called it a wonderful program and said seniors and people with disabilities often struggle to find housing. Mendoza urged the council to remove language that would allow landlords to require a cosigner to rent. “I think it’s important to remember, many people with disabilities and seniors don’t have families that can cosign, or may not have families at all,” Mendoza said. “I really think that if that is kept in, you’re making it difficult for a lot of people who would otherwise benefit from the program in Novato with the ordinance.” Officials in San Rafael said the City Council is poised to adopt its own fair housing rules at its Oct. 1 meeting.

0 Comments

BY EMILY NONKO | AUGUST 29, 2018

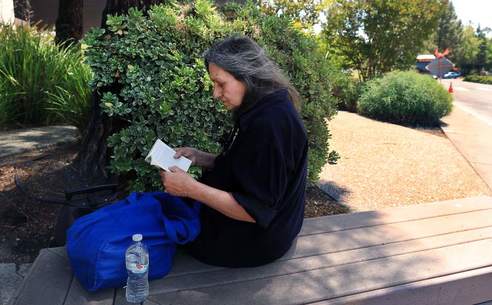

For Caroline Peattie to talk about the state of foreclosed homes in minority neighborhoods of Northern California, she has to get into the history of U.S. housing segregation. Peattie, the executive director of Fair Housing Advocates of Northern California, draws a line from early- to mid-twentieth century policies that enforced residential segregation by race and resulted in a persistent wealth divide, to the lead-up to the 2009 housing crash, in which minorities were targeted for subprime mortgages and then to the aftermath in which those minority neighborhoods were disproportionately affected by the foreclosure crisis. In the decade since the crash, she’s seen housing inequality persist in a new way. Fair Housing Advocates of Northern California is one of 19 fair housing organizations, led by the Washington-based National Fair Housing Alliance, filing suit this summer against Bank of America alleging the bank intentionally failed to maintain foreclosed homes in minority neighborhoods, while it consistently maintained similar bank-owned homes in comparable white neighborhoods. Fair housing organizations consider such disparate treatment of foreclosed homes to be reminiscent of redlining — the practice of denying bank loans and other forms of non-predatory lending to certain people or neighborhoods based on race. Both practices result in the gradual decay of housing stock in predominantly minority neighborhoods. Peattie rattles off statistics for Vallejo, a city where the group studied 24 homes owned by Bank of America. Two were located in Latino neighborhoods, 16 in predominantly non-white neighborhoods, and six in predominantly white neighborhoods. “When you look at the data,” Peattie says, “Two of these properties in neighborhoods of color had 10 or more marketing and maintenance deficiencies — one even had 15 — while none of the properties in the white neighborhoods had 10 or more of those deficiencies.” Issues like unsecured or boarded doors, damaged roofs, and peeling paint were documented in minority neighborhoods, she adds, but nearly non-existent in Vallejo’s predominantly white communities. As a result, it’s not only property values and therefore wealth creation that suffer disproportionately in minority neighborhoods — physical and mental health suffer, too. Low-income renters face difficult search for housing in Sonoma County after October wildfires8/16/2018 KEVIN FIXLERTHE PRESS DEMOCRAT | August 16, 2018, 4:35PM The notice to vacate was taped to Rotha Rice’s Rohnert Park apartment door the first week of May. She was expecting it, given she’d heard from neighbors that Americana Apartments was terminating the leases of every tenant enrolled in a federal housing subsidy program. Rice, 74, was given 90 days to leave the place she has called home since 2006, when she moved into the complex on the city’s northeastern edge with a single cup, a plate and a lamp. In the dozen years since, she accumulated a bed, furniture, a variety of books and other belongings. For the first time in a long time, she felt stable. The location of the apartment was ideal, situated only a mile and a half from her job of 26 years working graveyard shifts at a Shell gas station. It’s also not far from the city’s senior center where she grabs lunch daily, as well as a longtime network of friends who help get her to and from doctors’ appointments to manage her delicate health. Now that’s all been thrown into disarray as Rice struggles to find another landlord willing to accept her housing voucher. “On May 3, I called 27 places,” said Rice. “There’s nothing out there, because of the fires. “It’s plenty of time,” she added of the period to relocate, “but for me it’s no time if there’s nothing available.” Finding rental housing in many parts of Sonoma County is increasingly difficult for people like Rice, who rely on the Section 8 program to afford rents in Sonoma County. The waitlist just to get into the program for low-income renters can take up to six years, and those who have finally made it in are seeing the number of landlords who accept the housing vouchers shrink by the month. More than 4,700 people throughout Sonoma County are enrolled in the federal Section 8 program, which provides vouchers up to $1,633 per month for single-bedroom housing. The money available increases with the size of the rental. Admission is based on income. A single person who makes up to $34,400 annually is eligible to apply, while a family of four can make as much as $49,100. Once accepted, people in the program are required to spend 30 to 40 percent of their own income on housing, excluding the value of the voucher. By Tom Gogola, Pacific Sun - August 9, 2018

Federal Reserve study offers stark counterpoint to accepted wisdom that more development = cheaper rent. An eye-opening report on Forbes.com over the weekend was making the social-media rounds among regional politicos and housing advocates as it offered a sobering reality when it comes to housing: just because you build a lot of it, doesn’t mean the housing situation overall becomes more affordable to those of lesser means. The financial fanzine popular among the 1 percent crowd based its story on an April report from the Federal Reserve that dove into various housing statistics in a few big metro areas around the country—San Francisco included—and concluded that variations in rent in a given area are driven more by the availability of local amenities than they are by the numbers of housing units built. Bottom line, write co-authors Elliot Anenberg and Edward Kung, is that even as affordable-housing advocates push for mixed-income developments amidst a backdrop of environmental red-tape and local NIMBYism, there might be a better way: “Even if a city were able to ease some supply constraints to achieve a marginal increase in housing stock, the city will not experience a meaningful lessening in rental burdens.” The study’s authors instead suggest that policymakers considering deploying resources to improve amenities in lower-priced areas instead of pushing to build-out affordable housing in wealthy neighborhoods. If true, the implications of the Federal Reserve report are stark for regions such as the North Bay that have put their stock into a state-mandated “housing element” that’s heavy on the idea of mixed-income developments—to keep the local workforce local, the carbon-spewing cars off the road and the housing fair and just for all. The picture is complicated, mightily, by an expanding short-term vacation-rental market now afoot in a region that’s watched, for example, an entire middle-class neighborhood (Coffey Park) go up in flames in the past year. I sent the Forbes report to Caroline Peattie, executive director of Fair Housing Advocates of Northern California, to gauge her response. Peattie couldn’t offer a view on whether she thought the Fed findings were true or not, but “on the other hand, in some ways the conclusion seems to validate the concept behind why it’s important to affirmatively further fair housing — and all the things that go into achieving greater equity to all the opportunities related to where one lives. Something that the study labels ‘amenities’ may be more indicative of access to opportunity than the term would indicate. I’m most interested in looking at these issues through a fair housing lens, and since one’s zip code determines one’s access to transportation, jobs, education, health, environment, good food options—of course, the ‘high opportunity areas’ have these ‘amenities.’” Bottom line for Peattie is that whatever the approach to building affordable housing—it needs to be “seen through the lens of equity.” |

|

|

TDD: (800) 735-2922

Se habla español We welcome our site visitors with content in Spanish and Vietnamese. En Espanol TIẾNG VIỆT |

|